Randy's Rodeo

music that rocks, rolls, swings, and twangs

| Artist Index | Song Index | Radio | Home |

|

Music Reviews Special Features Information Support Me |

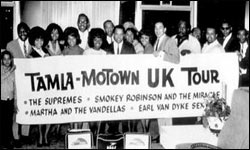

Support Randy's Rodeo!  Berry Gordy The Motown Story. The facts are well known. The story of Motown has entered our corporate mythology, right up there with Disney, Dell, and General Electric. How Detroit native Berry Gordy Jr. - a scrappy young entrepreneur and veteran of the Army, the boxing ring, and the Ford assembly line - began writing songs after his jazz record store went out of business. How he quickly achieved success, placing hit songs with Jackie Wilson, including "Reet Petite" (1957) and "Lonely Teardrops" (1959), then writing and producing hits like Marv Johnson's "You Got What It Takes" (1959). How Gordy was forced to lease his records to labels like Brunswick, United Artists, and Chess, and how he grew frustrated with his subsequent lack of control over production, promotion, and distribution. Smokey Robinson, who would become one of the first artists signed to Motown (and a crucial architect of their success), asked Gordy, "Why work for the man? Why not be the man?" So, Berry borrowed $800 from his family and started his own record label. The events of the ensuing decade are literally the stuff of legend. Motown Records became the most successful black-owned company in the world, placing hundreds of singles on the pop charts, and becoming the most famous independent record label in the history of the music business. As a pop phenomenon, Motown ranked second only to the Beatles during the 60's. Ultimately, Motown transcended the business world altogether, becoming famous as a sound unto itself. To many people, in fact, Motown is synonymous with rhythm & blues. (It's not, but more on that later.) The Motown phenomenon didn't happen overnight - though it was sudden and spectacular - and Berry Gordy's impressive historic stature is the product of Motown's publicity machine as much as the music itself. Moreover, so many people - musicians, songwriters, producers, and others - contributed to the success that made Gordy, for a while, the richest black man in America. But, with the exception of a handful of Motown's most famous artists - including Robinson, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, and Stevie Wonder - most of these people remain unknown outside a small and devoted cult of Motown maniacs (read more). The story is fascinating and richly dramatic one - far more so than I can impart on a few web pages. Luckily, numerous books have been written on the subject of Motown, most notably Nelson George's incisive Where Did Our Love Go? The Rise & Fall of the Motown Sound (1989) and The Motown Album: The Sound of Young America (1990), a lavish pictorial with history by Ben Fong-Torres and discography by Dave Marsh. I recommend them both, and others (see below). But what I'd like to explore is how the story of Motown reflects the story of America - and, especially, black America - before, during, and after the 1960's.  Lamont Dozier, Brian Holland, and Eddie Holland Like so many black residents of industrialized, northern U.S. cities like Detroit, Berry Gordy's parents immigrated from the south. The Gordys made their trek from Georgia in 1922, but after World War II, the pace of migration quickened thanks to the post-war economic boom. The Gordys, meanwhile, built a solid, stable, middle-class life, and they had lots of children in whom they instilled the value of independence and hard work. Until his success in the music trade, Berry was actually something of a ne'er-do-well compared to his more stalwart, traditional siblings. But, these were the days when African-Americans had to go along to get along - let alone succeed - in the white man's world. Even as the civil rights movement gained momentum, the strategy pursued by most black Americans was to blend in, their fondest dream to succeed despite their obvious (if skin-deep) difference from the majority of Americans. To dress neatly and conservatively, to speak without an accent, to defer with respect to others - these were signs of refinement (and the path to achievement) for many blacks in the 1950's. Such deference is easily misinterpreted in hindsight. When Berry Gordy founded Motown, the days of "black power" were still distant. Yet Thurgood Marshall, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, or Martin Luther King - though well-spoken and polite - were hardly shrinking violets. My point is, it's tempting for us to interpret the sequined gowns, crisp suits, and agreeable demeanor of the average Motown act as pandering to the white audience. Was it selling out? More like buying in! This was the world in which Berry Gordy was raised, and this is the image he projected through Motown - not the face of black America, but "The Sound of Young America." Somewhat infamously, Berry Gordy subjected his artists to rigorous training - not just as singers, but as young men and young ladies, and as entertainers. They learned to comport themselves with well-bred dignity. They learned how to walk, how to speak, and how to use a salad fork. They learned not just to hit the right notes, but to handle a microphone, to move with grace onstage, to project an air of respectability. Gordy, you see, envisioned his stable of artists playing not on the storied "chitlin circuit" but in theaters and stadiums, not just on the radio but on television and in the movies. Ultimately, they did.  2468 West Grand Boulevard Obviously, though, we're getting ahead of ourselves. At the outset, Berry Gordy's little record label was called Tamla, and its very first release was Marv Johnson's "Come To Me." This record, however, achieved success (#30 pop) only after being leased to United Artists for national distribution. "Motown" would soon become the name of Gordy's parent company and primary imprint, and over the years he released records under a large variety of labels, including Soul, Rare Earth, V.I.P., and Gordy. Tamla remained a prominent label, as well. In England - where Motown music borders on a religious obsession - the label is often referred to as Tamla or Tamla-Motown, the name of the company's UK subsidiary. Early on, Berry Gordy bought a little row house on Detroit's West Grand Boulevard, just down the street from a massive Cadillac factory, to serve as his headquarters, including office and rehearsal space as well as recording studios (referred to by its denizens as "The Snakepit"). Gordy ran the house - eventually, a group of houses - like a factory. "My own dream for a hit factory," Gordy later explained, "was shaped by principles I learned on the assembly line. I wanted the same concept for my company, only with artists and songs and records." Soon enough, the Motown complex bore the proud marquee, Hitsville U.S.A. (and now houses the Motown Historical Museum). At any rate, the pace of Motown's success accelerated rapidly. The Gordy dynasty officially began when Barrett Strong's "Money (That's What I Want)" (1959), originally released on Tamla, reached #23 on the pop charts in early 1960 after re-release on Anna Records (owned by Gordy's sister Gwen and later absorbed into Motown). Then Berry Gordy hit the Top 10 hit for the first time on his own label (Tamla) with the Miracles' "Shop Around" (#2, 1960). Led by writer and singer Smokey Robinson, the Miracles had already achieved some success with Gordy-produced records on End ("Got A Job," 1957) and Chess ("Bad Girl," 1959). Those records were fine, but they resembled doo wop more than the now-trademarked Motown sound. With "Shop Around," we start to hear it - the powerful beat, the clever wordplay, the emphasis on hooks and bright, hot production. But, while "Shop Around" is great, it's still a long way from streamlined Motown productions like "My Guy" (Mary Wells, 1964) or "Stop! In The Name Of Love" (Supremes, 1965). The Motown label itself debuted on the charts with "Bye Bye Baby" (#45 pop, 1961), written and sung by Mary Wells, who became Gordy's first bankable star and notched the label's first Top 10 hit ("The One Who Really Loves You," 1962). By then, nearly all of Motown's legendary artists had been signed to Berry Gordy's roster, but more importantly, the nascent king of industry had assembled the guild of artisans - mostly black and male - who would build his empire. Smokey Robinson, as mentioned above, would help write and produce dozens of hits for his Miracles and many other Motown acts. Barrett Strong became a staff songwriter and would later become the primary partner of Norman Whitfield, the predominant producer of Motown's hard-edged hits of the late 60's and early 70's. Billy Davis, Harvey Fuqua, Johnny Bristol, Frank Wilson, Mickey Stevenson, Clarence Paul, and Ivy Joe Hunter all contributed heavily to songwriting and production chores, as did Gordy himself. Maurice King taught the artists how to sing, Cholly Atkins showed them how dance, and Maxine Powell gave them manners.  The Funk Brothers But, two entities more than any other built the Motown sound. The first were the musicians. Led by keyboardist and arranger Earl Van Dyke, the Motown house band released just two records on their own - one as the Twistin' Kings and another as the Soul Brothers. But, in part or in whole, the Funk Brothers (as they came to be known) played on virtually every record that came out of Hitsville U.S.A. during its fabled "Golden Decade" (1962-1971). A large, loose, and shifting aggregation of seasoned professionals anchored by drummer Benny Benjamin and bassist James Jamerson, the Funk Brothers melded rock, gospel, and rhythm & blues into an altogether new alloy - not quite pop, not quite soul, but distinct, compelling, and bristling with energy. During Motown's heyday, the Funk Brothers toiled in anonymity for modest compensation, and both Jamerson and Benjamin died ignominious, premature deaths. Eventually the band achieved some long overdue recognition with Allan Slutsky's 1989 book, Standing in the Shadows of Motown: The Life and Music of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson, and a similarly-titled 2002 documentary movie. The second titan of Hitsville was the songwriting and production team of Holland-Dozier-Holland. At the outset, Eddie Holland served as one of Motown's early hitmakers, most notably with "Jamie" (1962). During the same period, both Lamont Dozier and Eddie's brother Brian wrote and recorded for Berry Gordy with limited success - though Brian Holland helped create Motown's first #1 hit, the Marvelettes' "Please Mr. Postman" (1961). Collectively, however, the trio struck a vein of gold that Motown mined through much of the 1960's, galvanizing their sound with Martha & The Vandellas' volcanic 1963 hit single "(Love Is Like A) Heatwave." More than any other producer at Motown, the Holland-Dozier-Holland team realized the sound that Berry Gordy heard in his head. Practically speaking, Lamont Dozier and Brian Holland wrote the music and produced the records, while Eddie Holland wrote the lyrics and arranged the vocals. They took the earthiness of gospel and blues, mixed in a dollop of funky, post-war rhythm & blues, and set it to a steadfast, innervating rock beat. Polished to a high-gloss pop sheen, these records virtually leapt from the speakers - undeniable and irresistible. This, in essence, was Berry Gordy's "Sound of Young America." Neither black nor white (yet attractive to both audiences), the Motown sound perfected by Holland-Dozier-Holland was visceral, romantic, hopeful, and upbeat - the perfect soundtrack for the optimistic and hedonistic early 1960's. As a result, the team amassed an astounding track record, charting 28 Top 20 pop hits over the next three years. These included such classics as "Mickey's Monkey" (Miracles), "Take Me In Your Arms (Rock Me A Little While)" (Kim Weston), "Can I Get a Witness" (Marvin Gaye), "This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak For You)" (Isley Brothers), and "Heaven Must Have Sent You" (Elgins). But generally, Holland-Dozier-Holland's grandest works were reserved for the Four Tops - including "Standing In the Shadows of Love," "Reach Out (I'll Be There)," and "Baby I Need Your Loving" - and especially the Supremes - including "You Keep Me Hangin' On," "Back In My Arms Again," and "Baby Love." Interestingly, though, Holland-Dozier-Holland rarely worked with the mighty Temptations, who were usually handled by Smokey Robinson or Norman Whitfield. (For more, see Heaven Must Have Sent You: The Holland/Dozier/Holland Story, 2005.)  Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield For a while, Motown could do no wrong. Berry Gordy's assembly line hummed night and day, cranking out hits distinctly Motown - yet individually distinct. But in the beginning, Motown records bore little annotation indicating who was responsible - songwriters were usually listed, perhaps producers, but never musicians. Even the artists were cloaked in mystery - a picture, maybe a sketchy biography, but little else. We know much more now (thanks to historians like David Bianco and Motown's own CD reissues), but even then it was clear that Berry Gordy exercised strict control over virtually everything, including his artists' appearance, repertoire, publicity, and royalties. We know now that Motown really was run like an assembly line - that was no mere metaphor. More precisely, Motown functioned like a research laboratory (and sweat shop). Berry Gordy and his producers worked round-the-clock, trying different lyrics with different music, different singers with different songs, and they kept refining records and rehearsing artists till both met Gordy's exacting standards. For instance, Jimmy Ruffin recorded a song in 1964 called "I Know How To Love Her," written by Norman Whitfield and Temptations singer Eddie Kendricks but unreleased at the time. Soon, Whitfield inserted new lyrics (cowritten by Barrett Strong), and the Temptations recorded it as "Too Busy Thinking About My Baby" for their 1965 LP, Get Ready. Then, in 1969, Whitfield persuaded Marvin Gaye wax his own version - and earned a Top 10 hit. As a result of such persistence, Motown maintained incredible quality control and phenomenal success. In 1966, for example, 75% of Motown's singles made the pop charts - a completely unparalleled achievement. As a byproduct, Motown generated an immense amount of material that never saw the light of day - great stuff, by any other standard - as well as an appreciable stable of artists who officially released few, if any, records for the label. Such ephemera drives Motown collectors completely bonkers, and a growing library of CD's like the Lost & Found series or Cellarful Of Motown, or rarities from forgotten Motown ingénues like Barbara McNair, has been created to sate our mania. As the 60's wore on, things inevitably changed. While the Vietnam War escalated and the Civil Rights movement grew increasingly uncivil, Motown's biggest hitmakers began to chafe under Berry Gordy's strict supervision. Success often breeds contempt. Predictably, then, Motown's monolithic domination of the Top 40 cracked, then fell apart over a five-year span (1967-1971). Most infamously, Holland-Dozier-Holland quit amid a flurry of lawsuits over unaccounted royalties, and they soon achieved modest success with their own Hot Wax and Invictus labels. But Motown's roster of artists was decimated as well. The Marvelettes and the Vandellas broke up, Diana Ross left the Supremes and Smokey Robinson quit the Miracles, and Gladys Knight and the Four Tops signed to new labels.  James Jamerson More fundamentally, the cultural changes and political events of the late 60's threatened to render the Motown sound obsolete. The label's hits - generally cheerful in demeanor and staunchly apolitical - seemed increasingly out-of-step with modern life in light of psychedelia, street riots, free love, Monterey, Woodstock, Altamont, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. The nation turned to gritty soul from Memphis and Muscle Shoals, or to the mind-blowing funk of James Brown and Sly Stone. Ironically, Motown - the most successful black-owned company in American history - wasn't black enough anymore. Motown did their best to modernize - most successfully under the guidance of Norman Whitfield - but the label was now following trends, not creating them. But let's not understate the obvious. Motown created lots of damn fine music as their Golden Decade wound down. Look at just a few of Whitfield's towering achievements: Marvin Gaye's "I Heard It Through The Grapevine" (1967), Edwin Starr's "War" (1970), the Undisputed Truth's "Smiling Faces Sometimes" (1971), and numerous masterpieces with the Temptations, including "I Wish It Would Rain" (1967), "Cloud Nine" (1968), "Ball Of Confusion" (1970), and "Papa Was A Rolling Stone" (1972). Plus, songwriters Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson joined the team in the late 60's, collaborating on such inspirational hits as "Ain't No Mountain High Enough" (Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, 1967) and "Reach Out And Touch (Somebody's Hand)" (Diana Ross, 1970). And, the Jackson 5 - the last great group from Motown's classic period - came aboard in 1969, cranking out bunches of sweet, soulful bubblegum and spawning the now-notorious King Of Pop, Michael Jackson - though his most successful records, Off The Wall (1979), Thriller (1982), and Bad (1987), were released by Epic Records. Even more, two of Motown's greatest artists waxed their finest records only after wresting free of Berry Gordy's firm hand. Marvin Gaye's What's Going On (1971) quite literally broke the Motown mold. Topical, tender, passionate, innovative, and fiercely intelligent, What's Going On provided Gaye and the Funk Brothers a platform to prove what level of genius stoked the fires of Gordy's hit factory. Through the 70's, Gaye produced a long string of excellent singles ("Trouble Man," "Got To Give It Up") and albums (Let's Get It On, I Want You). He jumped ship to Columbia for one final masterstroke ("Sexual Healing") before his tragic death in 1982.  On tour in England, 1965 Then there's Stevie Wonder. Signed to Motown in 1960 at the tender age of ten, he dutifully cranked out hits for most of the decade starting with "Fingertips" (1963). Even so, his already impressive catalog and his rapidly expanding talents - as a singer, songwriter, pianist, drummer, and more - did not predict the impact he would later have. Upon reaching the age of emancipation, he negotiated a new contract with Gordy granting him full artistic control. The albums that ensued - Music Of My Mind (1971), Talking Book (1972) Innervisions (1973), Fulfillingness' First Finale (1974), and Songs In The Key Of Life (1977) - stand as a nearly unequaled artistic achievement. Plus, they sold millions and earned numerous Grammy Awards. Which is a roundabout way of saying that while Motown's musical dynasty may have fallen apart, Berry Gordy's corporate empire did not. To the contrary, he moved his company to Los Angeles in 1972 and expanded into movies and television. Throughout the decade, Motown cultivated a number of best-selling acts, including the Commodores and Rick James. In addition, under Gordy's careful tutelage, Diana Ross became an international superstar as famous for her sartorial excess as her increasingly vapid musical output. And, thanks to movies like The Big Chill (1983), Motown became more famous for its past than present - and they exploited the hell out of it. Motown kept scoring hits through the 70's and 80's, though nearly all traces of the classic Motown sound had been erased by disco and funk. Even loyal Hitsville veterans like Diana Ross, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson, and the Temptations sounded resolutely modern - and that's perhaps the way it should be. Time marches on, and the world of rhythm & blues is mercilessly driven by the latest and hippest sounds. But, by the time songs like "Somebody's Watching Me" (Rockwell, 1983) and "Rhythm Of The Night" (DeBarge, 1985) scaled the charts, Motown was just another record label - profitable, efficient, and devoid of personality. Ultimately, Gordy sold the company in 1988 to MCA Records and Boston Ventures for $60 million. In 1993, the latter bought out the former, then flipped Motown to Polygram for $325 million. Then Polygram merged with MCA, now known as Universal Music. During these years, Motown's musical legacy was subject to repeated reissue - sometimes with wanton greed and disregard, sometimes with loving care - creating a formidable, patchwork catalog of compact discs (read more). But, in terms of sales and chart performance, the label achieved their greatest success in the 90's with hip-hop influenced acts like Boyz II Men, who spent nearly a cumulative year at #1 with five chart-topping singles.  Mary Wells In the end, Motown became perhaps the only record label whose name became synonymous with a musical genre. So distinctive is the Motown sound that many critics identify it as an idiom unto itself, separate from soul music and other rhythm & blues. In his book Sweet Soul Music, Peter Guralnick goes so far as to remove Motown from the 60's soul equation altogether. "I'm not referring to Motown," he writes, "a phenomenon almost exactly contemporaneous but appealing far more to a pop, white, and industry-slanted kind of audience." As evidence, Guralnick cites Atlantic Records big wig Jerry Wexler, who says of Motown, "They took black music and beamed it directly to the white teenager." Down in Memphis at Stax Records, recalls soul man Isaac Hayes, they took a similarly jaundiced view of Motown. "It was the standard joke with blacks, that whites ain't got that rhythm. What Motown did was very smart. They beat the kids over the head with it. That wasn't very soulful to us at Stax, but baby, it sold." Certainly, the man who wrote "Shaft" has credentials to make such a statement, but I take exception to his assertion that Motown didn't produce soulful music, and especially his inference that Motown didn't create black music. To the general public, the picture is even more cloudy. They lump early 60's girl groups like the Chiffons or Crystals in with Motown, or they include gritty soul singers like Solomon Burke with Motown's more refined roster. Over time, I've seen Al Green, the Stylistics, the Chi-Lites, and Aretha Franklin all confused as Motown artists - and none of them ever set foot in Hitsville U.S.A. My point is, just as Motown had groups of girls (like the Supremes) who weren't technically girl groups, they had exceedingly soulful singers (the Temptation's David Ruffin springs to mind) who nevertheless failed to meet the technical specifications of soul music. So, Guralnick may be formally right, but I refuse to cede the high moral ground. But what of Motown's broader legacy - how the story of Motown reflects the story of America? I would argue that it did, both in terms of the black struggle for freedom and equality, and in a more profound sense. Berry Gordy set out to become his own boss - not a civil rights leader - and he did. Hell, he became the boss, and that made a powerful political statement despite the polite image Gordy imposed on his artists or the deliberate beat that underpinned their records. Gordy became one of the richest men in America, not by capitulating to the marketplace, but by manipulating it. And, if that's not America - capitalism unbound - I don't know what is. In fact, Berry Gordy succeeded to such an extent that his success outgrew him, outgrew his company, and outgrew the music itself. As noted above, Gordy chose the phrase "The Sound of Young America" as Motown's motto. And, like Disney, or Chevrolet, or Superman, Motown became part of our shared American heritage - twisted into an impossible ideal, spit-shined by Madison Avenue, myth construed as fact, more meaningful as symbol than reality. Art becomes product, and product becomes art. Perhaps that's what George Clinton meant when he said, "America eats its young." Turns out, it eats the sound of its young, as well. [top of page]

Your witty comments, impertinent questions, helpful suggestions, and angry denials are altogether encouraged. Submit feedback via email; submissions will be edited and posted at my discretion. |

|

|||||||||||

Navigation Artist Index Song Index Randy's Radio Home Top Of Page Music Reviews Alternative Blues Books Christmas Classic Rock Country Jazz Lounge Special Features History Of Randy's Rodeo Sex Pistols Motown Records Halloween Valentine's Day Information About Me Feedback Links User's Guide Support Me Amazon iTunes Sheet Music Plus © 1999-2025 Randall Anthony, www.hipchristmas.com and www.randysrodeo.com |

|||||||||||||