|

Music Reviews

Alternative

Blues

Books

Christmas

Classic Rock

Country

Jazz

Lounge

Oldies

Power Pop

Punk & New Wave

Reggae

Rhythm & Blues

Seventies

Texas

Special Features

Randy's Rodeo

Sex Pistols

Motown

Halloween

Valentine's Day

Information

About Me

Feedback

Links

User's Guide

Support Me

Amazon

iTunes

Sheet Music Plus

|

Sock it to me, Santa! Visit my other website, www.hipchristmas.com Visit my other website, www.hipchristmas.com

Generational

issues come into play with Cream.

I know musicians about ten years older than me who get the same reverential, palpitating

response when listening to 60's Cream records that I get from 70's Television albums.

It's a matter of perspective, for Cream's sort of virtuosity was valued as highly in

their time as the guitar interplay of Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine was in their's.

To my ears, Cream went a little overboard at times - seventeen-minute drum solos, for

crissakes - but they produced an admirable, prolific body of work (four studio and

three live LP's, plus non-LP singles) in scarcely two years. And, Cream carved an impressive

series of milestones in rock history, being both the first supergroup and the first

power trio. More importantly, however, Cream was the first true blues-rock group. More

than merely a rock group who played the blues, Cream fused the two genres into a distinct

new sound. Generational

issues come into play with Cream.

I know musicians about ten years older than me who get the same reverential, palpitating

response when listening to 60's Cream records that I get from 70's Television albums.

It's a matter of perspective, for Cream's sort of virtuosity was valued as highly in

their time as the guitar interplay of Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine was in their's.

To my ears, Cream went a little overboard at times - seventeen-minute drum solos, for

crissakes - but they produced an admirable, prolific body of work (four studio and

three live LP's, plus non-LP singles) in scarcely two years. And, Cream carved an impressive

series of milestones in rock history, being both the first supergroup and the first

power trio. More importantly, however, Cream was the first true blues-rock group. More

than merely a rock group who played the blues, Cream fused the two genres into a distinct

new sound.

They accomplished that by achieving what few supergroups ever did: Cream was more

than the sum of its parts. Three topnotch English players - Eric Clapton (guitar),

Ginger Baker (drums), Jack Bruce (bass and primary vocalist) - joined forces in Cream

to create music more adventurous than any they had attempted before. Ginger Baker (who

had a traditional jazz background) and Jack Bruce had played together in both the Graham

Bond Organisation and the Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated, and Clapton played briefly

with Bruce in John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. Clapton and Bruce also collaborated in the

Powerhouse with Stevie Winwood (then with Spencer Davis) and Paul Jones shortly before

Bruce briefly joined Jones' group, Manfred Mann.

All

together, an impressive resume - but super? Not really. Truth be told, Cream was considered

a supergroup only in England, where blues revivalists like Alexis Korner and John Mayall

were - and still are - venerated. Of Cream's three founders, however, only Clapton

had earned any notoriety in the United States, where he was already being praised as "god" by

guitar buffs thanks to his incendiary work with the Yardbirds. Even so, Clapton had

quit the Yardbirds before they commenced their string of American hits with "For

Your Love," the song that prompted Clapton's exodus due to its overtly pop nature.

Clapton, you see, was thought to be a blues purist. All of which makes the case that

the startling innovation of Cream's music - which was a far cry from pure blues - and

the magnitude of their success could not have been anticipated, supergroup or not. All

together, an impressive resume - but super? Not really. Truth be told, Cream was considered

a supergroup only in England, where blues revivalists like Alexis Korner and John Mayall

were - and still are - venerated. Of Cream's three founders, however, only Clapton

had earned any notoriety in the United States, where he was already being praised as "god" by

guitar buffs thanks to his incendiary work with the Yardbirds. Even so, Clapton had

quit the Yardbirds before they commenced their string of American hits with "For

Your Love," the song that prompted Clapton's exodus due to its overtly pop nature.

Clapton, you see, was thought to be a blues purist. All of which makes the case that

the startling innovation of Cream's music - which was a far cry from pure blues - and

the magnitude of their success could not have been anticipated, supergroup or not.

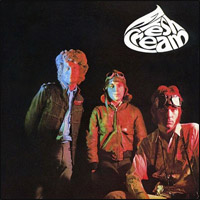

Cream's 1966 debut single, "Wrapping Paper," did little to foretell what

was to come. The follow-up, "I Feel Free," was better, a trippy, propulsive

pop song that provided a showcase both Bruce's robust voice and Clapton's concise,

stinging guitar. Later that year, however, the band's first LP, Fresh

Cream, finally showed the breadth of the group's talent and ambition. Mixing daring

originals ("Sweet Wine," "N.S.U.") with blues standards (Skip James' "I'm

So Glad," Willie Dixon's "Spoonful"), Fresh

Cream established a formula - if we can call it that - for the rest of Cream's

brief career: combining traditional and modern elements into an organic whole, on songs

both new and old.

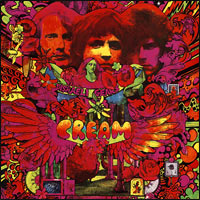

Disraeli

Gears (1967) stuck to that formula, with improved results; if not Cream's finest

album, it is certainly their first fully-realized effort. All but two songs on Disraeli

Gears were original compositions (all three band members wrote, often in collaboration

with producer Felix Pappalardi or lyricist Pete Brown), songs bracing both in the

creativity of their composition and passion of the performances. Songs like "Strange

Brew" and "Tales Of Brave Ulysees" are unlike anything in the annals

of rock, sounding somehow brand new and ageless at the same time. It's worth noting,

too, that Disraeli

Gears is a launching point for British heavy metal; Cream's overamped blues would

echo loudly across Led Zeppelin's debut album two years hence. At any rate, Cream's

heroic efforts were rewarded with commercial success, as both Disraeli

Gears and one of its singles, the proto-metal smash "Sunshine Of Your Love," attained

Top 5 status. Disraeli

Gears (1967) stuck to that formula, with improved results; if not Cream's finest

album, it is certainly their first fully-realized effort. All but two songs on Disraeli

Gears were original compositions (all three band members wrote, often in collaboration

with producer Felix Pappalardi or lyricist Pete Brown), songs bracing both in the

creativity of their composition and passion of the performances. Songs like "Strange

Brew" and "Tales Of Brave Ulysees" are unlike anything in the annals

of rock, sounding somehow brand new and ageless at the same time. It's worth noting,

too, that Disraeli

Gears is a launching point for British heavy metal; Cream's overamped blues would

echo loudly across Led Zeppelin's debut album two years hence. At any rate, Cream's

heroic efforts were rewarded with commercial success, as both Disraeli

Gears and one of its singles, the proto-metal smash "Sunshine Of Your Love," attained

Top 5 status.

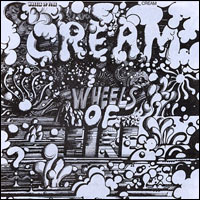

Cream followed Disraeli

Gears with a mildly successful single, Eric Clapton's "Anyone For Tennis" (featured

in the movie The Savage Seven), that, in retrospect, foreshadowed

the soft-spoken style the guitarist would adopt as a solo artist. The band's next

album, however, was anything but understated. Wheels

Of Fire (1968) consisted of two records - one studio, one live - that spoke to

the both the ambition and the burgeoning egos of Cream's three components. As for

ambition, the album spent four weeks atop the American charts and introduced another

batch of of impressive songs, including "White Room," "Politician," a

stalwart rendition of Albert King's "Born Under A Bad Sign" (written by

Booker T. Jones and William Bell), and Eric Clapton's definitive interpretation of

Robert Johnson's "Crossroads."

As

for ego, well, this is where the aforementioned age differential becomes apparent.

Simply releasing a double-album in 1968 took a lot of gumption, and Wheels

Of Fire's second LP - the live one - was comprised of just four songs, two of them

exceeding fifteen minutes (including "Toad," Baker's epic drum solo). Listeners

old enough to have listened to Wheels

Of Fire when it was first released no doubt heard a masterpiece - this is amazing

stuff, especially for its day. More to the point, for listeners lucky enough to have

actually witnessed Cream on stage, Wheels

Of Fire allowed them to re-experience three skilled improvisational musicians weaving

gold from mere threads of pop - by all accounts, it was magical. But, let's be honest,

most of us weren't there (or even born yet), and that kind of magic doesn't translate

well to vinyl. Nevertheless, Wheels

Of Fire and Cream's other concert albums - Live

Cream (1970) and Live

Cream Vol. 2 (1972) - remain among their most popular records. As

for ego, well, this is where the aforementioned age differential becomes apparent.

Simply releasing a double-album in 1968 took a lot of gumption, and Wheels

Of Fire's second LP - the live one - was comprised of just four songs, two of them

exceeding fifteen minutes (including "Toad," Baker's epic drum solo). Listeners

old enough to have listened to Wheels

Of Fire when it was first released no doubt heard a masterpiece - this is amazing

stuff, especially for its day. More to the point, for listeners lucky enough to have

actually witnessed Cream on stage, Wheels

Of Fire allowed them to re-experience three skilled improvisational musicians weaving

gold from mere threads of pop - by all accounts, it was magical. But, let's be honest,

most of us weren't there (or even born yet), and that kind of magic doesn't translate

well to vinyl. Nevertheless, Wheels

Of Fire and Cream's other concert albums - Live

Cream (1970) and Live

Cream Vol. 2 (1972) - remain among their most popular records.

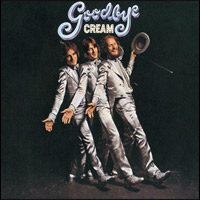

Meanwhile, the egos of Clapton, Bruce, and Baker were growing huge, indeed, and Cream

began splintering even as Wheels

Of Fire was hitting the racks. One final tour and it was over, though a fourth

LP, Goodbye

Cream (1969) was pieced together from studio leftovers (most notably "Badge," Clapton's

collaboration with Beatle George Harrison) and live cuts. Jack

Bruce immediately commenced a solo career, while Eric

Clapton and Ginger

Baker worked together in another supergroup, Blind

Faith (read more), before striking out on their own. Bruce

and Baker have led relatively acclaimed solo careers, but Clapton has inarguably eclipsed

them both, becoming one of the most popular, respected rock musicians ever (read

more).

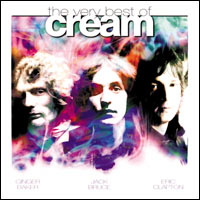

Despite

the obvious power of their albums - endless jams notwithstanding - Cream's singles

hold together very well on their own, and their record label (originally Atco, now

Universal) began releasing compilation albums almost as soon as the group broke up.

These include Best of Cream (1969) and Heavy

Cream (two LP's, 1972) - both never reissued on CD - and Strange

Brew: The Very Best Of Cream (1983). The latter album has been roundly eclipsed

by the similarly-titled The

Very Best Of Cream (1995, pictured), easily the best Cream anthology ever issued

- 20 songs encompassing every single Cream released, including a couple not on LP.

More dedicated fans, however, should simply purchase Those

Were The Days (1997), Cream's 4-CD boxed set featuring every official studio track,

a selection of live tracks, and several choice rarities - instant Cream, if you will.

Also of note: BBC

Sessions (2003), a revelatory compilation of radio broadcasts. Despite

the obvious power of their albums - endless jams notwithstanding - Cream's singles

hold together very well on their own, and their record label (originally Atco, now

Universal) began releasing compilation albums almost as soon as the group broke up.

These include Best of Cream (1969) and Heavy

Cream (two LP's, 1972) - both never reissued on CD - and Strange

Brew: The Very Best Of Cream (1983). The latter album has been roundly eclipsed

by the similarly-titled The

Very Best Of Cream (1995, pictured), easily the best Cream anthology ever issued

- 20 songs encompassing every single Cream released, including a couple not on LP.

More dedicated fans, however, should simply purchase Those

Were The Days (1997), Cream's 4-CD boxed set featuring every official studio track,

a selection of live tracks, and several choice rarities - instant Cream, if you will.

Also of note: BBC

Sessions (2003), a revelatory compilation of radio broadcasts.

Beyond their actual recordings, Cream had a tremendous impact on the world of rock

- not all of it good. While all three members - Baker, Bruce, and Eric Clapton - were

virtuosos, Cream's emphasis on virtuosity set the stage for greater and greater excesses

through the years. Particularly in the moribund realm of heavy metal - but also blues,

country, and jazz - the quantity and speed of notes played began to exceed the wisdom

with which those notes were chosen. But, we can't really blame Cream for this - or

for any other excesses that arose from their popularity. Cream's long flights of fancy

- depending on one's age or perspective - could be brilliant or boring, but much of

Cream's music is truly timeless.

|

|